Part 1

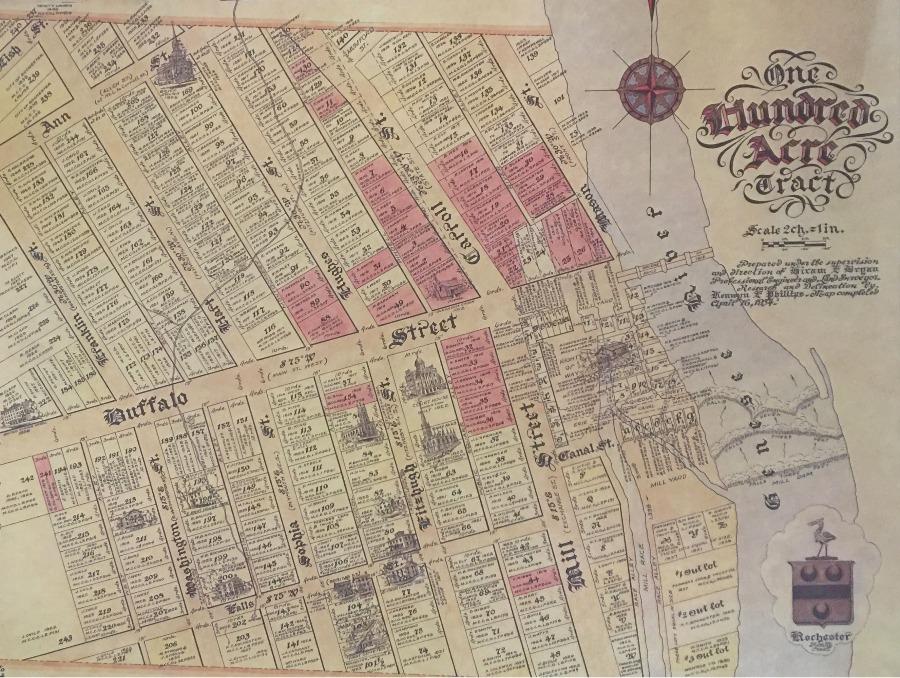

Modern day Rochester begins with the purchase of a one hundred-acre piece of land. In 1803, three wealthy veterans of the American Revolution set out from their homes in Hagerstown, Maryland. They came up through the Susquehanna Valley, found their way to the headwaters of the Genesee River and traveled along its western shore. They were speculators seeking undeveloped land in western New York as our newly formed nation began its inland expansion.

In those days, at the site where our city is now stands, the Genesee was a boundary between two counties—Ontario to the east with its county seat at Canandaigua; on the western side was Genesee County with its seat at Batavia. After purchasing land farther south, the three men, Colonels Nathaniel Rochester and William Fitzhugh and Major Charles Carroll went to Batavia to register their claims. The land agent suggested that they consider a piece of land located at the falls of the Genesee. He referred to a three-tier waterfall that once existed slightly north of where the Court Street Bridge stands today. It had two drops of three feet and a final drop of seven feet.

Rochester saw potential for tremendous power in in that cascading water, perfect for mills that could saw lumber or grind grain. Fitzhugh and Carroll agreed to be his partners in the purchase although the price was much higher than the $2-3 per acre they had paid for property farther south. The One Hundred Acre Tract sold for $17.50 per acre, or $1,750 for a small piece of land that would, in three decades, expand into a city. When the men returned home, their wives were not excited by the New York purchases, reluctant to leave behind comfortable lives in Hagerstown to take up residence in a wilderness. Plans were put on hold.

In 1810, Rochester finally moved his family to New York State, settling in the town of Dansville. In short time he created a flourmill, a sawmill, a paper mill, a blacksmith shop, a village store and began clearing a 450-acre farm. With so much accomplished, he considered giving up that expensive tract purchased with Fitzhugh and Carroll, both of whom remained in Maryland until 1816.

In 1811, Rochester visited the falls to review the property and found other settlements being developed nearby. The Brown brothers were planning to construct a mill just to the north. Across the river, Enos Stone was building a sawmill and had begun construction of a bridge over the Genesee. Charlotte and Irondequoit on Lake Ontario were also strong contenders. If Rochester didn’t act quickly, another location might become the area’s dominant town site, reducing the value of the Marylanders’ property.

In a way, the One Hundred Acre Tract was an unlikely spot for a successful village. The various waterfalls and rapids in the area, while providing power for mills, prohibited navigation where the Genesee flowed past the eastern end of Rochester’s property. Transportation of products to and from the mills would require long portages. A man-made river, the Erie Canal, eventually solved this problem but the canal was a dozen years into the future. Nonetheless, Rochester began laying out streets–one of them was Buffalo Street (today’s West Main) that would meet Stone’s bridge when it was completed. He divided most of his land into lots for homes and businesses.

In June 1812 the United States went to war against Great Britain. Since the British controlled Canada, their warships patrolled Lake Ontario and the mouth of the Genesee River. Those lake settlements became dangerous places for American families and many fled the waterfront. Earlier that year a Massachusetts man in search of western land, Abelard Reynolds, was on his way to Charlotte when he passed Rochester’s tract. He liked what he saw and bought two lots.

In July, Hamlet Scrantom moved his family into a log cabin on the site now occupied by the Powers Building, the first residents within the One Hundred Acre Tract. Shortly thereafter, Reynolds built a frame house on Buffalo Street, opened a saddle shop and became the first postmaster in the area. Scrantom wrote to relatives, “The Village is flourishing beyond all calculation.” The Reynolds family played a key role in that success for many years to come. I will continue that story next month.

Part 2

The winter of 1812-13 was a severe one. Settlers in the area surrounding the One Hundred Acre Tract hunkered down in their homes against icy winds and huge snowdrifts. Families rarely saw anyone beyond household members. An occasional visit from the local postmaster, Abelard Reynolds, was always most welcome. There wasn’t much mail arriving in those days; legend claims that Reynolds carried what little there was in his hat. However, the number of recipients grew quickly over the next few years.

In 1817, Nathaniel Rochester hand-carried an application for a village charter to the state legislature in Albany. It was approved on March 21 and Rochesterville was officially recognized. But there was a rival on the east side of the river—a village named Carthage was taking hold farther north where mills were harnessing the water power of the lower falls. Carthage had the backing of Canandaigua merchants and, with access to Lake Ontario, its prospects for becoming a major commercial center seemed more promising than Rochester’s little village.

Everything changed in 1823 when the Erie Canal was completed as far as Rochesterville. It would be two more years before the canal reached Buffalo but, with commercial traffic open all the way to Albany, Rochesterville’s size, population, and business opportunities grew rapidly. In April 1826, an “act to incorporate the village of Rochester” was passed, dropping the “ville” at the end of the Founder’s name, and dividing the community into five wards. The northern limit of the Third Ward was the Erie Canal and a portion of Buffalo Street (today’s West Main); the eastern boundary was the Genesee River.

When Abelard Reynolds first settled within the One Hundred Acre Tract, he operated a saddle shop in the front part of his home—the Tract’s first frame house (as opposed to log cabins). In 1828, Reynolds relocated his family and, at a cost of $30,000, replaced his house with a four-and-one-half story Arcade capped by a turret that looked out over the expanding village. Just one decade after Rochesterville’s original incorporation, people were astonished that so much of what they saw from that rooftop could have been accomplished in so short a time. Within the Arcade were shops, offices and, of course, Abelard’s post office. For decades, the building served as a center for Rochester’s business life. It has been suggested that Reynolds’ Arcade might have been the first indoor mall in the country, a claim now being investigated by staff of the Local History department at the Central Library.

In 1809, Reynolds had married the former Lydia Strong of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. They had six children, four of whom survived to maturity—two girls and two boys. The older daughter Clarissa married Dr. Henry Loomis Strong of Illinois (I have no idea if he was related to Lydia’s family). She gave birth to three daughters before dying at the age of 41. Mary Eliza married Byron Daniel McAlpine of Rochester; she had one daughter before dying at the age of 40. She is buried in the Reynolds plot of Mount Hope Cemetery.

In 1820, the elder son William Abelard Reynolds began his professional career as a barber (the second one in Rochesterville). Ten years later he pioneered a nursery and seed company. He maintained an office in the Arcade and a nursery on Sophia Street (now South Plymouth Avenue). He hired a young German immigrant named George Ellwanger to manage it for him—the same man who eventually joined with Patrick Barry to create the largest nursery business in America at that time.

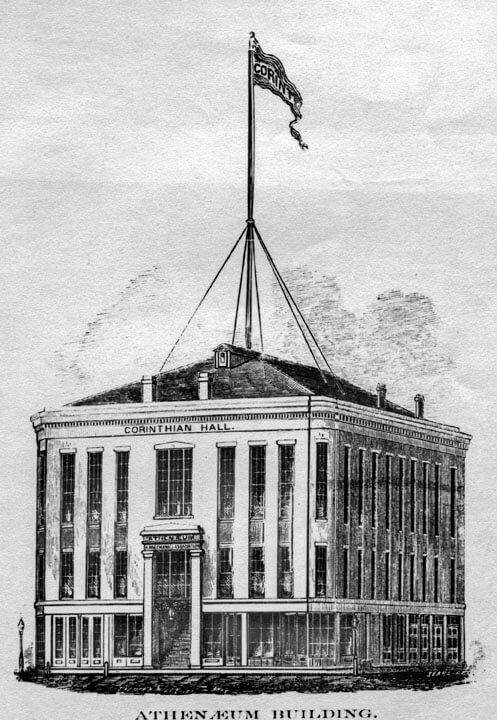

In 1845, Abelard was 60 years old and gave management of the Arcade over to his son William. Three years later William built Corinthian Hall behind the Arcade and it would be the scene for many of the city’s cultural events, including—just a year after it opened—the first public appearance by the Fox Sisters, spiritualists who dazzled a large audience with their ability to communicate with the dead.

In 1867, at the age of 82, Abelard suffered a paralyzing stroke. The family feared for the worst but he survived. Shockingly, it was 60-year-old William who died unexpectedly in 1872. The baby of the family, Mortimer Fabrius Reynolds, replaced his brother as manager of the Arcade. His Spring Street mansion was in the heart of the Third Ward’s “Ruffled Shirt District”—the subject of my next article.

Part 3

On June 12, 1829, a year after Abelard Reynolds opened his Arcade, sixty business leaders gathered in a room on its second floor to launch the Rochester Athenaeum. Nathaniel Rochester became its first president, a title he retained until his death two years later. Each member paid a five-dollar fee to fund a library that began with 400 volumes and would subscribe to Eastern newspapers and periodicals. The goal was to encourage adult education particularly in the fields of science and technology.

Expectations for the Athenaeum were initially high. It enjoyed so much success that the leadership applied for a New York State charter, which was granted on February 12, 1830. But soon it faced a powerful challenge from a very close source.

William A. Reynolds, Abelard’s son, felt his father’s organization was stodgy with little appeal for men his own age. In 1836, he founded the Mechanics Literary Association. In a short time, it acquired one hundred members who were drawn to its library of 1500 books.

A year later, an Irish immigrant named Henry O’Reilly formed yet another library-based institution. The editor of an early Rochester newspaper called The Daily Advertiser, O’Reilly is best remembered today as the author of a book, Sketches of Rochester (1838), that describes the founding and earliest growth of our city. O’Reilly’s concern was for young men most affected by Rochester’s high rate of unemployment at that time. He formed the Young Men’s Association to promote “the moral and intellectual improvement of the young men of the city.” It soon became the most prominent of the library societies. The Athenaeum saw that its only hope for survival was to merge with O’Reilly’s group thus creating the “Athenaeum and Young Men’s Association.” It offered a library of almost 3,000 volumes and a reading room “regularly supplied with thirty-five of the principal Reviews and Magazines in the United States and Great Britain.”

Gradually interest waned among the younger men—the very group it was meant to serve. Sinking into debt, the organization was forced to sell some of its books. When, in 1842, Henry O’Reilly moved away from Rochester, the institution was on the verge of collapse.

William Reynolds’ organization was also languishing when he came up with a bold plan. He combined the two organizations into one, the Rochester Athenaeum and Mechanics Association. Then he built a lecture and concert hall—Corinthian Hall—to house and support the newly formed group. Over the coming years, such speakers as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Horace Greeley and others filled the Hall’s eleven hundred seats so frequently that, by 1857, the Athenaeum was debt-free and its library fully supported. So great was this intellectual forum that one of its directors referred to it as a People’s College.

There was a brief possibility that the Athenaeum might become a real college when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862. Through the sale of federal lands, the United States offered funding for northern states (this was during the Civil War, of course, when southern states had seceded) to create colleges that taught “such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic[al] arts.” The “People’s College” in Rochester failed to qualify for funding, however, as New York’s money went to the yet-to-be chartered Cornell University in Ithaca.

As the Civil War ended, the nation went into an economic depression and Rochester was severely affected. Local investors suffered major financial losses, including William Reynolds who, in 1865, was forced to sell Corinthian Hall. The Athenaeum’s library struggled to maintain its collection despite the rising costs of books and periodicals. Its future looked even less certain several years later when the Corinthian’s new owners raised the rent. By then Reynolds was president of the Rochester Savings Bank and moved the association, rent-free, into its upstairs rooms. In 1872, William died and, three years later, the bank evicted the Athenaeum. Forced to pay rent at a new location, the organization again slipped into debt. By the summer of 1877, creditors demanded a public sale of the library to recover seventeen hundred dollars that was due them.

It would be up to Mortimer F. Reynolds of 150 Spring Street, Abelard Reynolds last surviving child, to find a way to save the collection. It wasn’t going to be easy.

Part 4

On December 19, 1878, Abelard Reynolds “fell into the placid sleep that knows no waking” (they just don’t write obituaries like that anymore!). He was 93. His wife, the former Lydia Strong, died in 1886 one month before her 102nd birthday. Their youngest child Mortimer would not have the longevity of his parents but he would devote his remaining years to saving the Athenaeum’s library as a lasting tribute to the family name.

Mortimer Reynolds was born on December 2, 1814, a year after his father moved the family from Pittsfield, Massachusetts. As an adult, Mortimer made the dubious assertion that he was the first white child born within the One Hundred Acre Tract.

On January 12, 1841, Reynolds married Mary Eliza Hart, daughter of Rochester pioneer Roswell Hart. Unable to have children, they adopted a daughter, Minnie Belle. Mrs. Reynolds was known throughout life for her charitable works. In 1879, she died of heart disease at the age of 59, less than eight months after her father-in-law’s death.

Mortimer made a fortune in the paint and linseed oil business and was quite generous with his money. He provided $5,000 to build a YMCA at the corner of St. Paul Blvd. and Main Street, and gave $25,000 to build a chemistry laboratory for the University of Rochester on Prince Street as a memorial to his late brother William.

William had died in 1872 and, with Abelard severely impaired by a stroke, Mortimer sold his business to take over management of the Arcade and Corinthian Hall. When the Athenaeum fell on hard times and a sheriff was ordered to sell the library’s books to settle outstanding debts, Mortimer and George S. Riley, bought the collection for $3,350. For ten years, the books remained in storage as the two owners considered ways to create a permanent fund that would support a library. Riley wanted to revive the Athenaeum but Reynolds was determined to create an institution that would perpetuate the family name.

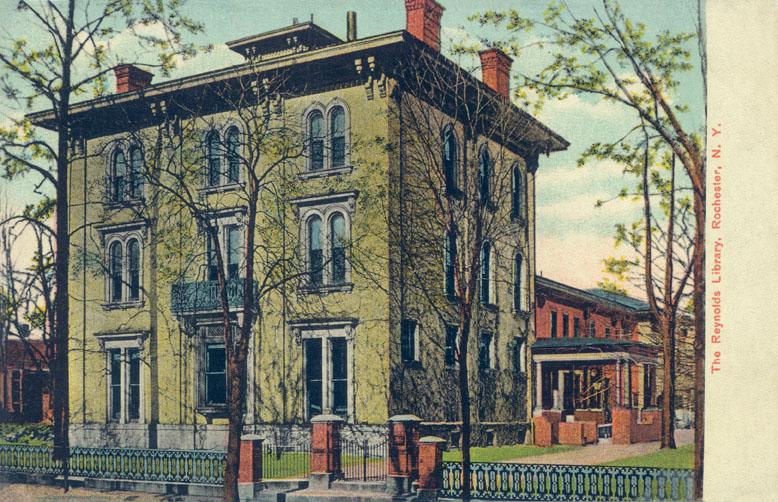

In 1882, Mortimer bought out Riley’s interest and began clearing space in the Arcade for the new “Reynolds Library.” Its charter stipulated that the rooms and property of the new library “shall not, nor any part thereof, be subject to taxation….” A local newspaper, the Union and Advertiser, vehemently campaigned against this provision, which would give a tax exemption to the entire Arcade, a private enterprise ever since its founding decades earlier. A heated debate erupted in the local press—the Democrat and Chronicle supported the measure—and the fight went all the way to Albany’s legislature.

In February 1884, the trustees settled for taxation that was “applicable equally” to other New York State libraries and, in January 1886, the Reynolds Library opened to the public in the venerable Arcade. It would not stay there for long.

Mortimer Fabricus Reynolds died on June 13, 1892 at the age of 79. In his will, he left both the Arcade and his home at 150 Spring Street to the library. In 1895, after extensive alterations had been done to the mansion, the Third Ward became the home of the Reynolds Library.

Over the next twenty years, Rochester created its own library system including a downtown facility in the old Kimball factory building. Then, in 1932, the city received money from the estate of Morton Rundell and began planning a new library that would be built on South Avenue.

Meanwhile, the Reynolds Library was financially challenged once again. When the Arcade, which supported the library, was ruled a firetrap, the one hundred-year-old structure was torn down and replaced by a new heavily mortgaged building. At the height of The Depression, the new Arcade had difficulty attracting renters to fill it. Trustees for the library worked out a merger that turned over the Reynolds collection to the new Rundell Library with the understanding that it would be designated as the “Reynolds Reference Library.” In the late 1940s, many libraries began to realize the educational potential of films and the Reynolds name was transferred to a newly created audio-visual department.

Today the central library has a newer building on the east side of South Avenue across from the old Rundell Library. The next time you check out a book at the first floor counter, turn around and you’ll see the Reynolds Media Center; a family name and a historic library still remembered.