Part 1

After moving into Corn Hill four years ago, I sometimes took evening walks through the neighborhood. I often ran into the late Janet Mlinar, patrolling the streets with her trusty camera. Two years ago we took note of the house at 97 Tremont Street. It was for sale and Janet seemed eager to learn more about its history. More accurately, Janet seemed eager for me to learn more and to write about it.

She promptly emailed me the real estate listing—the house was seriously overpriced for the market. Each time the price dropped, I heard from Janet. To all appearances, no lived in the house and I was reluctant to call attention to a home that was standing empty. I began a series of articles about William Kimball and the story of the Button House, as it is known, remained on hold.

In the past week, as I began writing this article, Ginny Brown shared copies of early Gazettes with me that dated back to the 1980s when a previous Corn Hill historian, Helen Newburg, wrote about topics of interest in the neighborhood. She had an advantage over me in writing about the Button House—she lived in it!

I’m finally ready to tell what I know, wishing I could have satisfied Janet’s curiosity before she died. I’m sure she would have enjoyed hearing about a curious family whose origins go back to an early time in our nation’s history. First, let me share some information about the origins of the house itself.

The Tremont Street house was built in 1850 according to a plaque on the front of the building but Helen Newburg said its history began much earlier. As the homeowner she may have had the property’s abstract which could have outlined transactions farther back in time. She refers to an early Rochester mayor, Charles J. Hill: “Mr. Hill bought four lots (on which the house is exactly centered) in the 1820s from Josiah Bissell Jr.” Bissell became one of the Third Ward’s earliest settlers when he and two partners built the first mill along the Genesee River in Nathaniel Rochester’s One Hundred Acre Tract.

With the opening of the Erie Canal, Rochesterville became a boomtown, resulting in a great deal of speculation in local real estate. In January of 1840, Hill took out two mortgages to build the front part of the Tremont house. Newburg suggests that the original house was probably “a two-story, hip-roofed Villa style with a cupola.” It was built with two front doors, one on the front of the home and a second one on the east side of the building, a feature that remains to this day.

Because Hill lived on South Sophia Street (now South Plymouth Avenue) during this period, the house on Tremont must have been rental property. By 1850, Rochester’s “boom” turned into a “bust” and Hill was struggling financially, unable to cover a one thousand dollar balloon payment on the property. Following foreclosure, the house went up for auction. Newburg tells us that, over the next fifteen years, the property would change hands five times and suggests that the place might have been jinxed because misfortune befell so many owners, beginning with Hill’s economic woes. The first owner after Hill was a real estate agent who purchased the property as an investment. He died of pneumonia a year later. The property passed to his daughter who sold it to an unnamed third party, the first owner to actually live in the house. A fourth owner lost the house when he was arrested for embezzling. In the early 1860s, George C. Buell bought the house, also as an investment. Buell ran a wholesale grocery business and lived in a very nice home on Livingston Park, next to the Hervey Ely House. During the three years he owned the Tremont property, his wife died.

The Tremont jinx apparently came to an end in 1865 when Buell sold the house to Nelson Lord Button. It would remain in the Button family for three generations, over a period of 108 years. On the other hand, there was a whiff of witchcraft in the Button family’s past and I wouldn’t be surprised if at least one family member who died in 1973 may still inhabit the home, upset that her final wish was not granted.

Part 2

In September 1628, Matthias Button arrived from England at Salem, Massachusetts. Within five years, he moved to Boston and is listed among that city’s earliest settlers. It was a difficult life as sickness claimed several children and Button’s first three wives. The third wife reportedly died of “fright and exposure” after John Godfrey, a Mathias enemy, set fire to the family’s home. Button took the man to court, accusing him of witchcraft and suing him “for the burning of my house, and my goods that was in it and the cause of my wife’s death….” The jury found in Button’s favor and ordered Godfrey to pay £238 in damages and costs.

Skipping ahead a number of generations, Nelson Lord Button was born in Ludlow, Massachusetts on November 5, 1826. At the age of 16, he became a teacher in a public school at Varysburg, NY. Four years later he married Jeanette Raymond who had been one of his students. The couple lived at Mount Morris, then at Malden, Massachusetts before settling in Rochester where they first show up on Tremont Street in the 1866 city directory. By this time he was working as an agent for The American Book Company, a position he would hold for forty years.

Mr. Button made many changes to the house: building an addition that enlarged the home to twelve rooms, installing lead plumbing and, perhaps haunted by the memory of that earlier ancestor, introducing improvements designed to protect the family from fire, including a water tank in the attic. There was also a windowless room—the “thunder room”—where family members could retreat during storms and be protected from lighting. Button also added the most distinctive feature to the exterior of the house. The five Egyptian-style columns on the front porch were reportedly hand-carved in Italy at a cost of $2,000.

The Buttons were active in the Methodist Church and Nelson participated in Republican politics, on one occasion serving as a delegate to a state convention. They had three children according to the 1900 Federal Census but by then only one survived. A sixteen-year-old son named Frederick is listed in the 1880 census but, in August of that year, he died of kidney disease and was interred at Mount Hope Cemetery. The Button family plot also includes a Jenny C. Button who died in 1860. No birth date or age is given but she is buried next to Frederick and could be his sister.

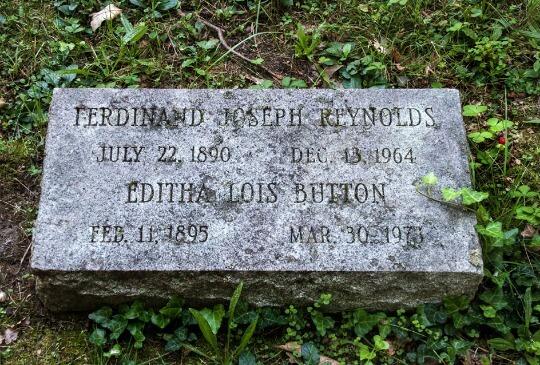

The third child was Nelson Jr. who was born in the Tremont Street home on February 1, 1873. On March 30, 1893, he married Alice Maude Goodger and, on February 11, 1895, a daughter, Editha Lois Button was born in the family home. She would be their only child. Three generations were now residing in the sprawling house. The Buttons would own the home for 108 years but there were several occasions when they went missing. In 1897, the Nelsons, father and son, moved to Palatine Bridge, New York. The reason is not documented, nor is it clear whether the women and servants traveled with them. The men returned in 1898.

The 1899 city directory says they “removed from [the] city” but this time they didn’t go far. The 1900 Federal Census finds them living in Brighton. A widow named Mrs. Katherine J. Dowling, head librarian at the Central Library, now occupied the Tremont home with her three adult children. They lived there for the next three years. The Button relocation may have been brought on by financial concerns. Years later, Editha admitted the family often lived beyond their means. “Oh, they had plenty,” she said, “but they gave it away faster than it came in.”

Although Nelson Sr. had a successful career, it’s harder to assess Nelson Jr. He shows up in records as an advertising agent but a place of business is never listed. Perhaps he was self-employed and worked from home. In 1901, while the family was living in Brighton, he operated a billiard parlor at 6½ Mill Street. Curiously, there is no #6 in the street directory so the business may have been above #10 Mill Street, which was a combined museum and saloon owned by Peter Gruber. Better-known as “Rattlesnake Pete,” Gruber served food and drinks in an establishment that also exhibited live “rattlers” and other reptiles.

Part 3

Editha Lois Button was the only child born to Nelson Lord Button Jr. and Alice Maude Goodger. She once described her father as “a playboy, a very precious boy, a handsome father, brought up to be a gentleman. Grandpa [Nelson Sr.] would never let him soil his hands….” Editha was similarly pampered.

For many years, the family had a housekeeper Resina Hollister who was so much a part of the family that, following her death in 1901, she was interred in the Button family plot at Mount Hope Cemetery. Because of Resina and perhaps other servants as well, Editha never had to do chores. “I’m not at all domestic. My mother used to see that I was always taken care of.”

She and her mother were close, often going on “motoring” trips as reported by the occasional line or two in the Personal columns of the Democrat and Chronicle. Both women were longtime members of the Nichols Travel Club, sometimes presenting papers about their adventures at monthly meetings held in the Bevier Building at the corner of Spring and South Washington Streets.

In addition to the twelve-room house at 97 Tremont Street, the family owned a sixteen-room summerhouse on a 70-acre farm on East River Road. The farm included horses, pigs, cats and dogs. As a child, Editha developed such affection for these animals that she became a vegetarian: “I could never eat my playmates.” She and her mother became fervent anti-vivisectionists and started an organization called the Humanitarian League Society to promote that cause. It was incorporated at the Tremont Street address where meetings took place for more than forty years.

When Editha was sixteen, she eloped with twenty-one year old Ferdinand Joseph Reynolds. I have not been able to find a record of this marriage in New York State Vital Records. Perhaps they went to another state. According to Helen Newburg, when the Button family learned of it, they had the marriage annulled. Despite that, the relationship continued. Newburg says Editha convinced her family to allow Reynolds a bedroom in the family home. City Directories often show Reynolds living at other locations but when he had to register with the draft board on April 27, 1942, he listed 97 Tremont as his address.

On October 17, 1951, the couple married again—I found this record so I know it’s true. Editha claimed she never took her husband’s name but a number of newspaper accounts contradict that assertion. Among them, her mother’s 1962 obituary lists “a daughter, Mrs. F. J. Reynolds,” among the survivors.

On December 13, 1964, Ferdinand died in St. Mary’s Hospital from a cerebral hemorrhage.

A century after her grandparents first moved into the Tremont Street house, Editha Button, last of the line, was alone in the big home with three toy poodles for company. Racial tensions had disrupted the Third Ward five months earlier and a helicopter had crashed into a home at the end of the street. The neighborhood was in decline and urban removal was soon tearing down many of its iconic homes. She refused to move out, however, insisting that there was a “feeling you get from living in the Third Ward.”

By 1970, things were improving. “I stuck it out in the neighborhood when everybody left and now all these young people are moving back in and making it fashionable to live [here again].”

On March 30, 1973, Editha Lois Button died of chronic lung disease. Her death occurred in the same bedroom where she had been born more than 78 years earlier.

In her final years, she could not conceive that anyone could possibly appreciate the house as much as the Buttons. In her will she declared that the house was to be demolished after her death. Obviously it wasn’t. Even as a nephew began getting quotes from contractors to tear down the house, the Landmark Society of Western New York stepped in with an application to declare the house a landmark and that stopped any attempt at demolition. A few days later, a fire mysteriously broke out in the bedroom where Editha had died. Helen Newburgh, who lived in the Button house in the early 1980s, said the floor was charred around the spot where the bed once stood. I have not been able to confirm if such marks are, in fact, there.