Part 1

I became the Corn Hill historian in October 2014. I knew little about our neighborhood’s past and immediately set about reading everything I could find. The first significant fact I learned was that, for most of our history, this was Rochester’s Third Ward. Over the years, I’d become aware of the Corn Hill Arts Festival but had never attended it and had no idea why our name was changed. My introduction to that story was Rob Goodling’s book Corn Hill and Its Arts Festival: the First Forty Years. The value of his book goes beyond the facts that Rob reports but in the numerous interviews he conducted to pull together a story about the people that created the first art show, how they grew it into an art festival and made numerous other changes over the years.

History is not about facts alone. The Third Ward/Corn Hill story is about its people: who they were, what they did, how they contributed to the neighborhood, the city, or even the world. Unfortunately, because most of my research is in the Nineteenth Century, I can’t interview people the way Rob did. And so, I begin with findable facts and wait for their stories to emerge.

For several years I have had an interest in a man named Charles Mulford Robinson. I first became aware of him when neighbors Robert Conklin and Sue Porter stopped by my house several years ago and presented me with a book Robinson wrote entitled “The Third Ward Catechism.” It was a witty collection of questions followed by the proper responses that should be cited by everyone who lived in the ward. E.g.:

How may Third Warders be known? Their blood is blue and their shirts are said to be ruffled.

How can one become a Third Warder? By birth or marriage or immemorial usage.

I found several of his other writings at the Central Library and they all confirmed that he was droll in a somewhat old-fashioned way. In one of his written pieces, he commented on the Third Ward’s tradition of open houses on New Year’s Day and I made him a character in my December tour that pays homage to that custom. But I still didn’t fully “get him.”

I soon learned that he was active in city planning and I liked to tell people that Robinson designed my hometown of Fort Wayne, Indiana. Then, during the past year, I learned something that helped me realize he was part of a much larger movement and created American cities far beyond Indiana. At last, his story emerged.

Charles Mulford was born to Arthur Robinson and Jane Howell Porter on April 30, 1869 in Ramapo, Rockland County, New York. According to the 1870 Census, Arthur was a stockbroker who had already acquired some wealth. Their household included two domestic servants and a coachman. By 1872, the family had relocated to Rochester into a house that still stands at 67 South Washington. Within a few short years, the family added three daughters.

The Robinsons had deep roots in our nation’s history going back to 1635 when an ancestor first reached America’s shores. More than two centuries later, Charles’ great-grandfather, Reverend William Robinson married Elizabeth Norton. She was the daughter of Ichabod Norton, who fought in the Revolutionary War. Through Ichabod, Charles Mulford would, in 1894, claim membership in the Sons of the American Revolution. His grandparents were Charles Robinson and Nancy Maria Mulford who each contributed to his distinguished name.

Robinson’s pedigree was just as impressive on his mother’s side. In 1816, Jane Howell Porter’s grandfather, Augustus Porter purchased Goat Island, located between the Niagara River’s Canadian and American Falls, because he saw its potential as a tourist attraction. Within a couple of years, Augustus built a pedestrian bridge connecting it to the American side and, today, the island remains accessible only from New York.

Augustus never cleared away the island’s dense vegetation, a decision that would later be heralded by Frederick Law Olmsted who said that in all his travels he had never seen “the same quality of forest beauty…still to be observed in those parts of Goat Island where the original growth of trees and shrubs had not been disturbed….”

Soon Olmsted and Charles Mulford Robinson would bring innovation to American cities.

Part 2

As mentioned, Charles Mulford Robinson arrived in the Third Ward as a two-year-old child when his parents moved to Rochester from Rockland County in 1871. He grew up in the house at 67 South Washington Street.

As a student at the University of Rochester, he demonstrated a talent for writing, serving one year as class poet and the next as historian for the Class of 1890. He had a friend from Scranton, Pennsylvania named Allan Gold Robinson who boarded at 37 South Washington, the Jonathan Child mansion, which was at that time a fashionable boarding house.

I have not found a family connection beyond the coincidence of their last names, which they duly noted in the title of a comic opera they created during their student days: “Robin Hood by Robin’s Sons.” Men filled all the roles including Maid Marian. There were three other Maidens, named First, Second and Third. Those numerical “ladies” sang a song, “Three little maids from ‘Coll’ are we,” indicating a debt to Gilbert and Sullivan; perhaps additional music was purloined from other composers as well. Most of the roles lampooned faculty members, although the university’s founding president, Dr. Martin B. Anderson (about to retire), was discreetly spared any such silliness.

After graduating from the University, Charles became writer and editor for the Rochester Post Express, a newspaper owned at the time by another Third Warder, William Kimball. In the coming years, Robinson would also write or edit other publications— Philadelphia’s Public Ledger, Harper’s Monthly, The Atlantic Monthly and Architectural Record. That last publication speaks directly to Robinson’s primary mission throughout his professional life.

In the 1890s, American cities were becoming overcrowded due to a high birth rate, immigration from other lands and the influx of many people from rural areas. In response, a movement called the City Beautiful began to rethink the design of cities, proposing monumental public buildings, recreational areas and more efficient transportation systems as solutions. The first great example of this movement occurred in 1893 when Daniel Burnham created the White City for Chicago’s Columbian Exposition.

Robinson had spent four months traveling in Europe during the spring and summer of 1891 and took note of how its capitals were ahead of the United States in civic design. When the White City opened, he was once of its earliest visitors and praised its design in a report entitled The Fair of Spectacle, extolling “the wondrous beauty of its outward form.” Over the years he continued to advocate the City Beautiful Movement; his 1901 book The Improvement of Towns and Cities became its Bible. He attacked practices that ignored “all teachings of the past, unconscious of all the possibilities of the future. We are laying out the new districts of Greater New York, not as the ideal city, nor the city beautiful, nor even as a city of common sense. We are merely permitting it to grow up under the stimulus of private greed and of real estate speculation.”

One chapter in Robinson’s book is entitled “The Tree’s Importance,” describing it as a “highly useful and decorative part of street furnishing, which years of growth are required to create, though an hour’s thoughtless work may destroy…. How comes it,” he wondered, that “the tree’s planting and care are still so neglected, that rich cities submit to miles of treeless thoroughfares and that good neighborhoods have been content with a few straggling specimens?”

He advocated municipal ownership of trees and was pleased when, on January 1, 1900, Rochester passed an ordinance putting its trees under the supervision of the Park Commission. For years, Robinson would serve as our city’s park commissioner and it is likely through his association with the man who created New York City’s Central Park, also a proponent of the City Beautiful Movement, that we have four Frederick Law Olmstead parks in Rochester.

Advocates of the Movement believed it could bring social harmony by improving a city’s quality of life. Critics thought it put too much emphasis on structures—an “architectural design cult”—while ignoring the need for social reforms to address underlying causes of poverty and crime. Nonetheless, many city officials turned to Robinson for help and he designed Denver, Colorado Springs, Omaha, Honolulu, Los Angeles and others, including my home town of Fort Wayne, Indiana!

Part 3

In 1896, Charles Mulford Robinson married Eliza Ten Eyck Pruyn of Albany, New York. Her pedigree was just as illustrious as her husband’s. She was one of five children born to Augustus Pruyn and Catalina Ten Eyck, only three of whom survived infancy. Eliza came from a prestigious Dutch family. Her father fought in the Civil War and her mother, Eliza Bogart, became a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution thanks to her grandfather, Captain Isaac Bogart who served in that war. Eliza could have become a member of the D.A.R. herself but I am not certain she did. She was, however, clearly proud of those family origins because her name often shows up in records as Eliza T. E. P. Robinson.

The couple lived for a time at 118 Troup Street. Then on October 1st, 1897, they moved into 65 South Washington, next to Robinson’s parents. The marriage would not produce any children but they seem to have lived very comfortably as Charles continued to promote the City Beautiful Movement. In the 1910 Federal Census, 40-year-old Charles was listed as a Writer. Eliza was 39, no occupation designated. Two young Irish women, apparent sisters, were living with them as servants: Abina M. Ahern, 27, was cook and Julia C. Ahern, 22, the chambermaid.

About that same time, Robinson’s success was reaching new heights. In October of 1910, he was one of two delegates representing the United States at an international conference on city planning. Sponsored by the Royal Institute of British Architects, its membership included King George VI, future father of Queen Elizabeth II. Charles and Eliza used the conference as an opportunity to take a month-long tour of Europe during which they visited many of its largest cities.

In 1913, the University of Illinois awarded Robinson with the first chair of civic design created in the United States. In October 1916, the Council of the Town Planning Institute in London granted him honorary membership, a recognition that had only been extended to one other American at the time—Frederick Law Olmstead. Robinson also wrote a number of books about civic design, wrote articles for numerous publications and sometimes even served as the editor of those journals.

In December 1917, between Christmas and the New Year, the Robinsons visited Eliza’s sister and brother who shared a home in Albany. Margaret at fifty years of age had never married. She maintained the home while Foster, 42, worked in real estate. During the visit, Charles became seriously ill with lobar pneumonia. In those pre-antibiotic days, his condition deteriorated rapidly. His mother traveled from Rochester to be with her son when he died on December 30th. He was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery on January 2, 1918. His mother was unable to attend the funeral. She was still in Albany, ill from the same strain of pneumonia that killed her son. She died on January 4th and was buried next to him on the 7th. Four years later, February 1922, Robinson’s father, Arthur, died at his South Washington Street home.

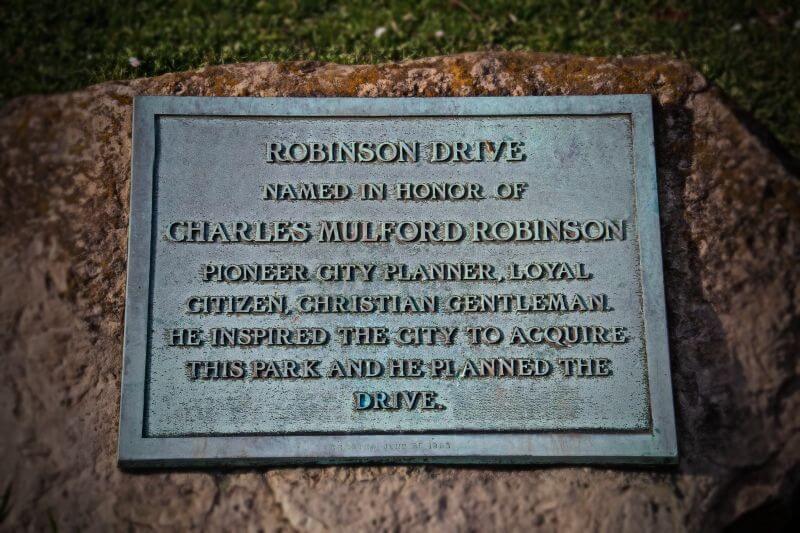

In 1926, Bonivard Street, across from the north entrance to Mount Hope Cemetery, was renamed Robinson Drive. A tribute in the Democrat and Chronicle said, “Mr. Robinson was decades ahead of his time in his prophetic vision of city-planning possibilities. He foresaw what Rochester was to become as have few men that have lived in this community.” In June of that year, a ceremony was held at the northeast corner of Mount Hope Avenue and that newly named drive where Eliza Robinson unveiled a bronze tablet honoring her late husband.

Eliza continued to live at 65 South Washington. Julia Ahern, the chambermaid in the 1910 census continued to live with her and in the 1940 census was listed as Eliza’s companion. In 1941, Margaret and Foster Pruyn were in Lakeland, Florida—the family may have had a winter home there. In April they suffered fatal injuries in an automobile accident. She died on April 19; he died the next day. Eliza was executor for both of their estates.

On May 18, 1956, Eliza T. E. P. Robinson died in Lakeland. She is buried next to her husband Charles at Mount Hope Cemetery. Julia Ahern died in Lakeland on May 4, 1969. She is buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery.